New Jersey's Green Infrastructure: The Role of Lagoons in Wastewater Treatment

- Ankur Manchanda

- Sep 20, 2025

- 3 min read

When we think of wastewater treatment, images of complex industrial facilities often come to mind. However, in many parts of New Jersey, particularly its more rural and less densely populated areas, a simpler, nature-inspired solution plays a vital role: the wastewater treatment lagoon.

These unassuming bodies of water are a testament to the power of natural processes in managing and purifying our water resources.

What Exactly is a Wastewater Lagoon?

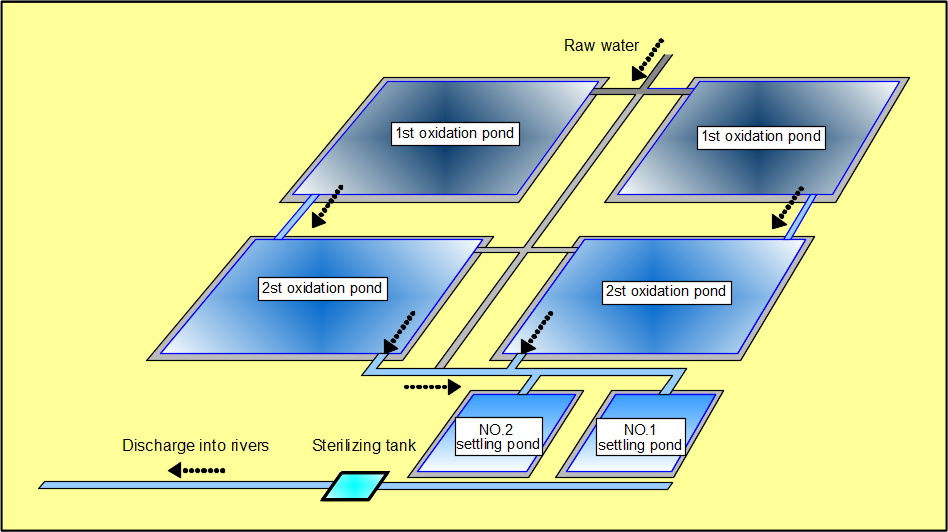

Essentially, a wastewater lagoon is a large, shallow, man-made pond designed to hold wastewater for an extended period.

During this retention time, a sophisticated interplay of physical, chemical, and biological mechanisms works to break down organic pollutants. Think of it as a carefully managed ecosystem where the sun, wind, bacteria, and algae collaborate to cleanse the water.

The Natural Treatment Process:

The effectiveness of lagoons stems from several key natural processes:

Bacterial Action: Microorganisms, primarily bacteria, are the workhorses of the lagoon. They consume organic matter in the wastewater, converting it into less harmful substances like carbon dioxide and water.

Algae's Contribution: Microscopic algae thrive in the sunlight, performing photosynthesis. As a byproduct of this process, they release oxygen into the water. This oxygen is crucial for the aerobic bacteria, which are the most efficient at breaking down organic waste.

Sedimentation: Heavier solid particles in the wastewater gradually settle to the bottom of the lagoon, forming a layer of sludge. This physically removes a significant portion of the pollutants.

Sunlight and Wind: Sunlight penetrates the shallow water, promoting algal growth and providing warmth that enhances bacterial activity. Wind aids in oxygen transfer from the atmosphere to the water, further supporting aerobic conditions.

Different Lagoons for Different Needs:

While the basic principle remains the same, lagoons are often categorized by their oxygen levels, which dictate the type of bacterial activity that predominates:

Anaerobic Lagoons: These deeper lagoons operate in the absence of oxygen. They are typically used as an initial treatment step for highly concentrated industrial wastewaters, such as those from certain agricultural or food processing operations. Anaerobic bacteria break down complex organic molecules, often producing methane gas.

Facultative Lagoons: The most common type, facultative lagoons are designed with distinct zones. An oxygen-rich (aerobic) layer at the surface supports algae and aerobic bacteria, while an oxygen-depleted (anaerobic) layer at the bottom handles sludge decomposition. A middle "facultative" zone accommodates bacteria that can adapt to varying oxygen levels.

Aerated Lagoons: To enhance treatment efficiency, especially in areas with limited land or colder climates, aerated lagoons utilize mechanical systems (like surface aerators or diffused air) to continuously introduce oxygen into the water. This significantly boosts the activity of aerobic bacteria, allowing for faster and more thorough treatment.

New Jersey's Regulatory Landscape:

All wastewater treatment systems in New Jersey, including lagoons, must operate in strict compliance with the New Jersey Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NJPDES) program.

Administered by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP), the NJPDES program implements the federal Clean Water Act by setting stringent limits on pollutants discharged into the state's surface and groundwater. Operators of lagoon systems must regularly monitor their effluent quality to ensure they meet these standards.

Why Lagoons in the Garden State?

While metropolitan centers in New Jersey rely on advanced mechanical treatment plants, lagoons offer several compelling advantages for smaller communities, rural developments, and certain industries:

Cost-Effectiveness: They generally have lower construction, energy, and maintenance costs compared to conventional mechanical plants.

Simplicity of Operation: Lagoons require less technical expertise to operate, making them ideal for smaller municipalities with limited resources.

Resilience: Their natural processes can often handle fluctuations in wastewater flow and strength more robustly than highly mechanized systems.

Environmental Benefits: When properly managed, they can offer a sustainable, low-energy approach to wastewater purification.

However, lagoons are not without their considerations. They require significant land area, which can be a constraint in densely populated parts of New Jersey. Additionally, regular maintenance, including the periodic removal of accumulated sludge, is essential to ensure their long-term effectiveness.

Looking Ahead:

As New Jersey continues to balance environmental protection with sustainable development, wastewater lagoons will likely remain a crucial component of its infrastructure.

By harnessing the power of natural biological processes, these green treatment systems provide an efficient and environmentally sound method for safeguarding the Garden State's precious water resources, one pond at a time.

Comments